One question I’ve been mulling over lately is how in blue blazes did a document with Ronald Tammen’s name on it housed in the FBI’s Cincinnati office find its way into the agency’s “circular file” mere months after Detective Frank J. Smith of the Butler County Sheriff’s Office had reopened an investigation into Tammen’s disappearance?

After all, Butler County is in the Cincinnati office’s jurisdiction. If a Butler County detective is actively working the case, you’d think those folks would realize that the record might be of interest. Also, it wasn’t as if the FBI didn’t know that the case had been reopened. They were supposedly providing assistance to Butler County and their counterparts in Walker County, Georgia, as the two offices had joined forces to determine if the remains of a John Doe buried in Lafayette, Georgia, happened to be Tammen.

Their timing seems…oh, I dunno…questionable?

And so, as per yoozh, I needed to investigate.

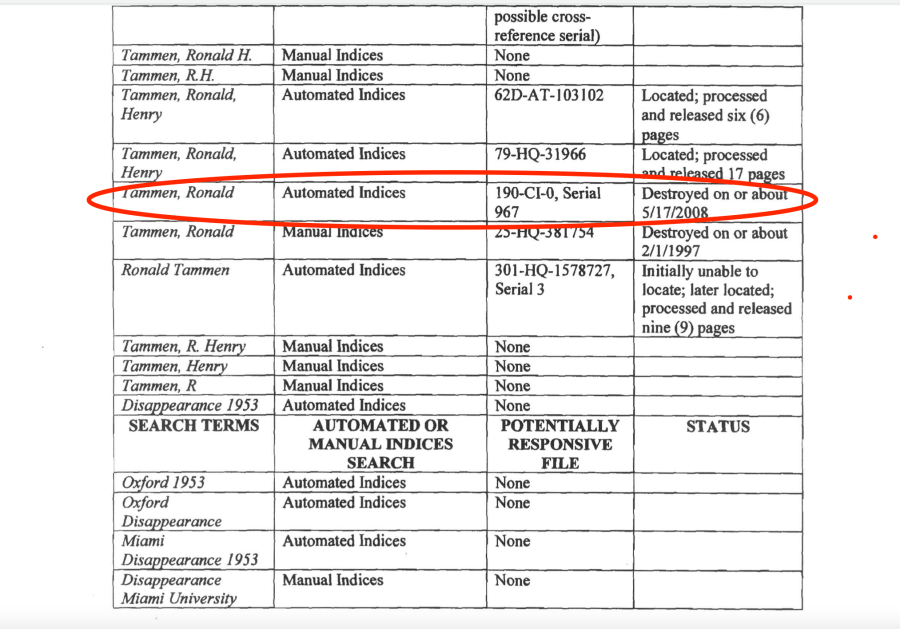

As we’ve discussed previously, the record in question is #190-CI-0, Serial 967. According to the FBI’s Record/Information Dissemination Section, it was “destroyed on or about 5/17/2008,” five months after Detective Smith and his Georgia counterpart, Mike Freeman, decided to reopen their respective cold cases.So why (again, in blue blazes) did the Cincinnati office feel that the time was ripe to destroy that particular document THEN?

Because they’d been so helpful in the past, I submitted a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request to the National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), asking them for the Standard Form 115 (SF 115) that substantiated the FBI’s destruction of #190-CI-0, Serial 967.

Their FOIA specialist got back to me the next day. You heard me right. He got back to me—with an actual response—on the very next day that I submitted my FOIA request. When it comes to FOIA, NARA is the biggest, baddest bunch of rock stars ever in comparison to all the other federal agencies. They’re the Beatles, Rolling Stones, Tina Turner, The Who, Led Zeppelin, Queen, Aretha, Bruce, I’m gonna say Dire Straits but that’s just me, [fill in name of your all-time favorite artist/band], and James Brown all rolled into one. Put simply, dealing with NARA’s FOIA office is a feel-good experience.

And where do our friends at the FBI and CIA fall on the rock spectrum? I’d say that one could be likened to Milli and the other to Vanilli. (It makes no difference which is which.) They’re usually just mouthing some words, giving us some lip service. If there’s a document they don’t want the public to see, they’ll find a way to withhold it, regardless of whether their reason is justifiable or not, and they’ll stall for as long as humanly possible. It has to do with r-e-s-p-e-c-t. NARA respects FOIA and the public it serves. The FBI and CIA, um, don’t. Strong words, I know, but girl, you know it’s true. (P.S. The Milli Vanilli analogy doesn’t extend to the musicians and singers who backed them up, especially the drummer, who was playing his heart out in the above video. I have more to say about the drummer near the end of this post.)

Here’s what NARA’s FOIA representative told me:

Agencies do not submit documentation to NARA to substantiate destruction of records. They use approved records schedules to determine the disposition of the records.

Oops. I should’ve checked the online records schedule before submitting my FOIA. But, truth be told, this stuff is confusing and sometimes I need to have things spelled out for me. Also, even if I’d consulted the records schedule first and it had said “Discard after such-and-such timeframe,” I couldn’t imagine that it would have applied to this scenario—during a newly reopened cold case investigation. Surely, there must be a clause that states: “If a document scheduled for destruction is potentially relevant to a newly reopened cold case, of course you should hang onto said document. Good Lord, did you even have to ask?” Or something to that effect.

The NARA rep then explained the file’s numbering system.

FBI File #190-CI-0 is as follows:

1. Classification 190 – Freedom of Information Act/Privacy Acts

2. CI – stands for the field office, Cincinnati, OH

3. “0” – the 0 files were used for administrative and logistical matters but mostly were used for citizen correspondence related to a classification, routine request for information, and general reference materials.

Allow me to interject here that one key difference between the Freedom of Information Act and the Privacy Act is that, with a FOIA request, you’re generally seeking information about someone other than yourself or a specific government program. With a Privacy Act request, you’re seeking information about yourself. OK, carry on, NARA FOIA rep.

NARA FOIA rep then added:

Classification 190 files do not include the underlying records.

What he means by this is that the record being requested under FOIA or the Privacy Act—like a fingerprint record, for example—wouldn’t be part of the Classification 190 file. But correspondence that pertains to that record—e.g., “Dear Sir or Madam: Please expunge my fingerprints because blah blah blah and OH MY GOD CAN YOU EVEN IMAGINE HOW A SENTENCE LIKE THAT MIGHT HAVE ENDED?!”—would. That’s just an example off the top of my head, mind you. We’ll never know what Ronald Tammen’s document actually said because, as I believe I’ve pointed out several times already, the FBI’s Cincinnati office destroyed it in the middle of Butler County’s reopened investigation.

NARA’s FOIA representative then sent me a link to the FBI’s applicable records schedule, N1-065-82-04,and he referred me to the pages having to do with field offices, which was Parts C and D. There’s a lot of overlap and plenty of room for judgment calls. Also, this is the honor system, an idyllic system of hope and trust whereby doing the right thing is expected and doing the wrong thing, well, I suppose that can happen too.

What Part C says

Of all the parts of the 309-page records schedule, Part C is the shortest and friendliest, offering up just three pages of general guidelines for FBI field offices regarding what to do with their aging records. I’m posting all three pages for you here.

At the top of page one, it says:

“These authorities apply regardless of the classification” but then they have some caveats concerning what might be discussed in other parts (e.g., Parts D or E), with this important NOTE: “Care must be taken to insure that records designated for permanent retention by other items in this schedule are not erroneously destroyed using authorities in this part.”

Translation: field offices should do what’s in Part C, regardless of classification, but if other parts of the schedule say that you need to do something else, do that. And most importantly, when in doubt, don’t throw it out.

Actually, that reminds me of a story someone told me. When J. Edgar Hoover was director of the FBI, he didn’t want to let go of anything. For decades, the FBI hoarded all of their records and wouldn’t even let folks from the National Archives touch their stuff. It wasn’t until after Hoover died that they finally let NARA in the door to work out a disposition schedule. The FBI changed their policy in part because they were getting a new building in Washington, D.C., so they used that opportunity to get permission from NARA to destroy a lot of their records. (Incidentally, the FBI still isn’t 100 percent onboard with NARA and FOIA and the whole public transparency cause. Although they dutifully send their records over to NARA on the agreed-upon timetable, they have yet to send an index to help NARA navigate their FBI holdings and address any subsequent FOIA requests they may receive.)

Back to Part C. Because Ron’s document was in the “0” file, the Cincinnati office was instructed to “DESTROY” it when it was 3 years old or “when all administrative needs have been met, whichever is later.”

I suppose it’s possible that the document had coincidentally reached its three-year mark in May 2008. However, even if that were the case (which I don’t believe for one second) I can’t imagine that whoever destroyed it then had determined that all administrative needs had been met when, you know, a cold case investigation had been reopened the next county over. I know at least one detective who might have had an administrative need or two for that document.

There’s another item in Part C that might apply as well. Because Ron’s document is in the Classification 190 category, we know that it had to do with FOIA or the Privacy Act (most likely the latter). Item #9 deals specifically with cases in which the subject requests disposal because “continued maintenance would conflict with provisions of the Privacy Act of 1974.” If that were the reason for destroying the document, then Cincinnati ostensibly should have submitted an SF 115 to NARA beforehand. However, if they’d submitted one, I’m pretty sure I would have received it from NARA when I’d FOIA’d them. (NARA’s FOIA rep’s exact words were: “There are no other records responsive to your request.”) Either item #9 didn’t pertain or, well… ¯\_(ツ)_/¯.

Confused? Stay with me. You’re doing great.

There’s a chance that the folks in Cincinnati also consulted Part D, the guidelines for each of the individual classifications for field offices. This is where things really get complicated. Under Classification 190, we’re told to “See Part C (which we’ve already seen), except for those cases where disposition is governed by General Records Schedule 14.”

Oh, good, a new records schedule. It’s as if they knew I was growing tired of the first one.

When you go online to find General Records Schedule (GRS) 14, you’ll soon learn that in 2017, it was superseded by General Schedules 4.2, 6.4 and 6.5. However, back in May 2008, federal agencies were still doing things according to the 1998 version of GRS 14.

And if you take a gander at that schedule, you’ll soon be presented with a menu of very strict and specific instructions that depend on what the record is—which, alas, we don’t know because the FBI’s Cincinnati office destroyed it.

But wait. Maybe we can figure out what kind of document it was based on the two dates we already know. We know that Ron’s fingerprints were expunged in June 2002 due to the Privacy Act or a court order, most likely the former. And we also know that in May 2008, the Cincinnati office destroyed a Tammen-related document having to do with FOIA or the Privacy Act, most likely the latter—though we’re less certain about that one. If both actions were due to the Privacy Act, they could be related, with a difference of six years between them. And if we look at the 1998 version of GRS 14, only one Privacy Act-related document specifies waiting six years before it can be destroyed. It’s this one:

- Erroneous release records—files relating to the inadvertent release of privileged information to unauthorized parties, containing information the disclosure of which would constitute an unwarranted invasion of personal privacy.

Maybe that’s the reason they destroyed Ron’s record? It’s impossible to say. But honestly, as I’m wading through the bureaucratic jargonistic blather that is today’s post, annoyed and discouraged and bored out of my mind, I don’t think it matters if the Cincinnati field office was operating under Part C or Part D (or even Part E, the catch-all “Miscellaneous” category for files kept elsewhere) or the old GRS 14—whatever—I still believe they could have turned over Ron’s “0” file document to their law-enforcement partners in Butler County when they had the chance. And make no mistake about it, they had the chance. I’ll tell you why shortly.

Serial 967

There’s one part of Ron’s record that we haven’t discussed the meaning of yet—the number at the end, Serial 967. Serial 967 is what identifies Ron Tammen’s record from everyone else’s in the “0” file. To help you visualize things, picture a metal filing cabinet with a bunch of drawers in it and Classification 190 occupying one of those drawers. (I’m sure it occupies more space than that, but this is just to help us understand the organization.) Now picture the “0” file as a folder inside that drawer in front of all the other folders. The “0” folder holds a large number of documents, and each document has its own serial number, which are arranged in numerical order. When Cincinnati still had Ron’s record, it would have been located pretty far back, between serial numbers 966 and 968.

I have no idea what kinds of documents shared a folder with Ron Tammen’s document, but it might be interesting to find out, mightn’t it? For this reason, I’ve submitted a FOIA request for the documents that surrounded Ron’s—beginning with serial number 900 and ending with number 999. Today, I received a letter of acknowledgement from the chief of the FBI’s Record/Information Dissemination Section letting me know that it was an acceptable request and assigning it a number. If I receive anything of interest, I’ll be sure to let you know.

More on Milli Vanilli’s drummer and how he relates to the FBI’s Cincinnati office

Milli Vanilli’s drummer was Mikki Byron, an accomplished musician who not only played the drums really well, but he also played the guitar, saxophone, and keyboard and sang vocals. In addition to his time spent with Milli Vanilli and the Real Milli Vanilli (the true singers behind Milli Vanilli plus band members), he played in a number of bands, including Mikki Byron and The Stroke, Custom Pink, and the L.A. Ratts. Tragically, Mikki died in 2004 at the age of 36. (As for Milli Vanilli, Rob Pilatus, one-half of the duo, also died tragically in 1998. Fab Morvan, the other half, is still performing.)

Whether or not you’re a fan of Mikki’s music, here’s the point I wish to make: Despite sharing a stage with two guys who were fake singing and whose purported dance moves were just plain awkward, Mikki Byron was for real. He had innate talent and he had training, and he brought everything to the stage when he performed. Fans miss him. They still talk about him. There’s a tribute page on Facebook for him. If you didn’t watch the video of Mikki playing the drums when I mentioned it before, please watch it now. You won’t be sorry.

I was hoping that I’d found my own version of Mikki Byron within the FBI—someone in their ranks who’d be willing to break free of all the stonewalling and duplicity and actually answer a couple simple questions truthfully.

This past Saturday, I sent an email to the Cincinnati office’s community outreach specialist. I said:

I’m wondering if you can help me. For a book and blog that I write, I’m interested in learning more about the Cincinnati field office’s protocol with regard to potentially relevant records during reopened cold cases.

Specifically, if a cold case has been reopened in a county within your jurisdiction, and the FBI has been made aware that the case has been reopened and is providing assistance, what is the Cincinnati field office’s protocol if it possesses one or more potentially relevant records?

The outreach specialist responded that day and told me they’d forwarded my email to the appropriate person. That person—whom we’ll refer to as Mikki—responded on Monday morning. Mikki’s emails will be in blue to help you keep track.

Thank you for your message.

For your background, if the FBI is assisting a local law enforcement agency on a case, relevant records can be shared with the investigators of that agency. If this does not fully answer your question, please provide me with additional details and I will try to provide a more specific answer.

Holy crap, right? Perhaps I’ve finally landed someone who’s willing to address my questions about how they handled Ron’s document.

Here’s me again:

Thank you so much for your quick response. I really do appreciate it. What I’m trying to understand is why the Cincinnati field office destroyed document #190-CI-0, Serial 967 in May 2008 (see attached) when the Butler County Sheriff’s Office had reopened a cold case investigation into the subject of that document, Ronald Tammen, in January 2008 and the investigation was ongoing. It’s my understanding that the records retention schedule for “0” files in field offices appears to allow flexibility for document retention for administrative needs, which I’d think would apply in this case. From what I can tell, it doesn’t appear as if the document was shared with Butler County before it was destroyed, unless you can determine otherwise.

Any information you can offer would be truly appreciated.

And back to Mikki:

Thank you for the added details. My previous response was very general in nature and not pertaining to any specific case or investigation.

Since you are interested in specific case information, it would be best to submit a FOIA request (which you may have already done) or contact the National Press Office (npo@fbi.gov) about any records management questions.

Thank you.

Riiiiiiight. We tossed it, but you’ll need to talk to those helpful folks over at FBI headquarters about why we went ahead and tossed it.

Here’s me again:

OK, will do. Are you able to say whether you shared the document with Butler County?

And back we go to Mikki:

Haha, just kidding. It’s been 5 days. Mikki hasn’t responded and I’m quite certain that he won’t.

On second read, maybe I came on too strong with Mikki. He asked for details and I gave him some. I’m afraid that my details drove Mikki away.

But you guys, if there was nothing to this mystery—if it was a big fat nothingburger, as they say—he could have said something like: “The document had already been destroyed by the time we learned about Butler County’s renewed efforts. We destroyed it on the basis of Part C, item #2, when the document was three years old.” You know…a credible explanation that could have sent me on my way.

Most telling was that he didn’t answer my question about whether they’d shared the document with Butler County, when, under normal protocol, that’s something they would have done.

There are a few things I can still do to try to learn more about the Cincinnati document on Ronald Tammen, and I will do them, though I won’t put the most promising ones into writing at this point. Will I be asking the FBI’s press office about the file? Oh, yeah, I suppose I’ll do that too, just as I told Mikki, but I can’t imagine that they’ll say anything other than “The FBI has a right to decline requests.” (I’ve heard that one before.)

I also want to make good on a promise I made to you earlier in this post. Some of you may have been wondering to yourselves whether it was possible that Cincinnati had destroyed the Tammen document without ever knowing that Butler County had reopened its cold case on Tammen. I mean, pleading ignorance is a very understandable and forgivable excuse, and Cincinnati is a big city and Butler County is about 35 miles away. Also, you may recall that it was the FBI’s Atlanta office that had opened the “Police Cooperation” matter for the two sheriff’s offices. Is it possible that Cincinnati had no idea that Butler County had reopened its cold case?

Oh, they knew. They so knew.

Here’s how I know they knew: In August 2010, just as I was getting started with my little book project, I interviewed Butler County Detective Frank Smith about his investigation. I’d submitted my FOIA request to the FBI for Ron Tammen’s documents several months earlier, and I was still waiting for their response. Frank had also obtained Ron’s FBI documents—the same ones that I would eventually receive. But Frank, being with law enforcement, would be able to go another route to get his documents—one that was much quicker. Frank had contacted someone with the FBI’s Cincinnati field office, likely by phone. He told them that he’d restarted the Tammen investigation and asked if they could send him whatever files they might have on Tammen.

Can I pin down the precise date that it happened? I can. After Frank Smith retired from the sheriff’s office, I obtained his old file on Tammen. He’d created a log of actions and developments complete with dates and times. Frank Smith had obtained his FBI file on January 22, 2008, at 6:30 p.m. to be exact—just as his investigation was getting started and nearly five months before someone within the Cincinnati office decided to destroy its Classification 190 file on Tammen.

When the bastards grind you down, check out the Black Vault’s files on cafeteria complaints. They haven’t gotten in the FBI’s or DOJ’s yet, but the CIA’s are quite amusing. Also their employees can’t spell.

Sounds fun…thank you!

I just watched this video for the umpteenth time, and I can’t believe I didn’t include every one of these people in my list of rock stars–especially Prince. Oh my God, Prince! https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6SFNW5F8K9Y&list=RD6SFNW5F8K9Y&index=1

I recently heard back from the FBI’s press office regarding my questions about why the Cincinnati office had destroyed Ron’s Classification 190 record in 2008, 5 months after Butler Co. had reopened its cold case. Here’s our conversation. (Spoiler alert: 🤦🏻♀️.)

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

Me:

Dear FBI press office,

I was referred to you by the FBI’s Cincinnati field office. Can you or someone knowledgeable please provide a response to the following two questions:

1) Why did the Cincinnati field office destroy document #190-CI-0, Serial 967 in May 2008 when the Butler County Sheriff’s Office (within Cincinnati’s jurisdiction) had reopened a cold case investigation into the subject of that document in January 2008?

2) Did anyone from the Cincinnati field office share file 190-CI-0, Serial 967 with Butler County before it was destroyed?

I’m attaching two documents as background: one is a RIDS-generated document that states when the Cincinnati file was destroyed. The second is an excerpt from a log kept by the Butler Co. cold case detective indicating the date and time he received FBI documents from the Cincinnati field office for his investigation. The latter item is proof that the Cincinnati field office was informed of the renewed investigation sometime before January 22, 2008.

As mentioned in the subject head, I’m seeking this information for a book and blog project. Any information you can provide would be appreciated. If you could provide a response by Friday, August. 20, I’d be grateful.

Sincerely,

Jennifer Wenger

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

FBI response:

Hello Jennifer,

I hope this finds you well. This is Linda from the Office of Public Affairs (OPA). Thanks for contacting the FBI. I have be asked to review and respond to your below email request. After reviewing, I decided to advise you that we do not have records back to 2008. However, you can file an FBI FOIA Request at:

Federal Bureau of Investigation

Attn: FOI/PA Request

Record/Information Dissemination Section

170 Marcel Drive

Winchester, VA 22602-4843

Or send a Fax to:

Fax: 540 868-4391/4994

Or find us on the Web at:

foipaquestions@ic.fbi.gov

https://www.fbi.gov/services/records-management/foipa

Thanks for your continuous interest in the FBI.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

To her credit, she responded on the 19th, a day before my requested deadline. But I think you can see how FOIA is frequently used by these folks as a smokescreen. Of course I’m submitting FOIA requests too, but it would have been nice if someone would just answer my two simple questions.

As for whether someone knows more than what they’re willing to say to me, I have no question about that.

//Because I need to tread carefully when FOIAing documents in this general area of interest, I’ve decided to start with emails, which are fair game. For the first request, I’m seeking all emails between HQ and the Atlanta and Cincinnati field offices (i.e., between Cincinnati and HQ, between Atlanta and HQ, and between Cincinnati and Atlanta) concerning the reopened cold case (Case ID #62D-AT-103102) for the time period of 1/14/2008 through 6/30/2009.//

Oh, yeahhhh. Here’s hoping….

Hey, thanks…🤞😊 On another front, I’m thinking I may have discovered something rather interesting about Switzer during academic year 1956-1957. If you haven’t read the latest FB update yet, make sure you do. I’ll go ahead and say it: I think Switzer probably wrote the Dec. 1956 letter to Griffith W. Williams, and I have another one from Feb 1957 that I think he wrote to Williams as well. I believe he was on a sabbatical that year and doing some full-time work with someone rather important. I’m pulling together evidence to support my hypothesis but this could be interesting. Stay tuned.

Stevie J, I received a response on my FOIA request for HQ-Atlanta-Cincy emails, and I’m attaching it. Not sure if you’ll be able to read it (sometimes the images are too small with this software), but it says that they’re not opening a FOIA request because of my lawsuit settlement. I’ll appeal because I feel that emails would fall outside of the settlement.

The lawsuit settlement has been an albatross around my neck, I must admit, and lately more often than usual. It was difficult to negotiate with them when we were in the dark about what they actually had. If there’s one positive that we came away with, it was the declaration listing all of the different places they’d looked for Tammen docs. If we didn’t have that declaration, we wouldn’t know anything about Ron’s Cincinnati record being destroyed in 2008, among other things. It’s been a learning experience.

P.S. I removed the attachment — it was way too small.

A little update:

I kept my promise to Mikki and emailed the FBI’s press office asking for their response regarding why the Cincinnati field office had destroyed document #190-CI-0, Serial 967 in May 2008 when the Butler County Sheriff’s Office had reopened a cold case investigation into the subject of that document in January 2008. I also asked them if anyone from the Cincinnati field office had shared the document with Butler County before it was destroyed. I’m doubtful that I’ll receive a meaningful response, but we’ll see what happens.

Because I need to tread carefully when FOIAing documents in this general area of interest, I’ve decided to start with emails, which are fair game. For the first request, I’m seeking all emails between HQ and the Atlanta and Cincinnati field offices (i.e., between Cincinnati and HQ, between Atlanta and HQ, and between Cincinnati and Atlanta) concerning the reopened cold case (Case ID #62D-AT-103102) for the time period of 1/14/2008 through 6/30/2009. For the second request, I’m seeking all emails between HQ and Cincinnati concerning document #190-CI-0, Serial 967 for the time period of between 1-1-2008 and 5-30-2008.

I’m doing other things too, although I need to keep mum on those.

Thanks for your input, and I’ll keep you posted.

You’ve alluded to this before, and I don’t want to spoil anything you want to write about in future posts. If these records were destroyed because of the privacy act, do you believe that Ron himself, perhaps under a new identity, was the one who requested the records be destroyed? If he were a.I’ve, it’s reasonable to think he could have read about the Georgia investigation, but would that lead him to start filing motions to have decades old records destroyed?

Interesting question. Here’s my current thinking, although, admittedly, there’s still quite a bit of conjecture involved. I currently believe Ron made a Privacy Act request, though I’m inclined to think he’d made his request in 2002, asking the FBI to expunge his fingerprints to protect his privacy. The fingerprints were gone in 2002 but his request to expunge them could live on—until the record came due to be destroyed. But what you’re asking is also interesting—what if the Georgia investigation had led Ron to make another inquiry? Perhaps he would have thought to contact them again just to make sure everything was destroyed. To me, it seems more feasible that someone from the Cincinnati field office found a record of his request to expunge from 2002 and they decided to destroy it because of the renewed investigation…again, to protect his privacy and also to prevent a media firestorm. However, you ask a really interesting question and I’ll definitely keep it in mind as I continue digging. By the way, one thing I also love is that, if Ron made the Privacy Act request, whether in 2002 or perhaps as late as 2008, how wild is it that he may have contacted the Cincinnati field office to do so? Thanks for your question.

I have to think there was an unofficial policy regarding records destruction. Official rules aside, are we to believe a LEO request for information would not stop an otherwise scheduled purge in its tracks? Hypothetically, what if 4 months later they’d found another body along I-75 and the FBI announced they’d pitched the file? Seriously, they’re lucky you didn’t get to them earlier. Anyway, I’d love to hear from a former employee on that point.

Furthermore, are we supposed to think that purge just happened to occur a couple months after a possibly huge break had occurred in a 50 year old case?

This nonsensical behavior is what tips me-the most anticonspiracy member of the posse-into the conspiracy side. Yeah, I know, it could be stupidity or incompetence or apathy, but come on, man. The FBI and CIA can’t do any better than this?

I agree with you. Here’s the embarrassing part: I had the document in 2014 that showed that they’d destroyed the Cincinnati record in 2008. I think I just looked at it and thought,”huh….that was recent. That’s a shame.” Also, I think I even knew that it had something to do with FOIA or the Privacy Act. I think I thought it was probably a FOIA request, which could be anyone…even someone like me. But I didn’t think: “Oh, they must have gotten rid of that on purpose, without telling Frank Smith about it.” That’s all new, and I think what got me to this point was finding out why they expunged Ron’s prints. Then everything started to gel.

So I think you’re right. Documents can only get me so far, especially when evidence is being destroyed. It’s people I need. That’s where I am right now.

CCR.

I scored mui bragging rights at work over MV. Someone told our crew how much they liked them, and I dismissively suggested you could put any two people on earth up there and it’d sound just as good. The story broke maybe a week later. That was probably the high point of my life.

In for a dime, in for a dollar. FOIA a summary list of what they provided Atlanta. Then find a Nikki in Atlanta.

Lol! First, oh my gosh YES, CCR. And I refuse to believe that the MV scandal was the high point of your life. 😆 Great idea about Atlanta. I’ll add that to the list. Also, at first I wasn’t that excited about approaching the FBI’s press office again, but now that I have proof of when Frank Smith received his file, it might be kind of fun after all.