At some point in our lives, all of us has learned the valuable lesson that…pardon my French…💩 happens. By this, I mean that not everything is going to go exactly as planned. Sometimes, there’ll be the occasional hiccup, even though no one is really at fault.

As a matter of fact, 💩 happened to me very recently. That’s not surprising for someone who spends a lot of their time doing what I do. But you know what? As all-powerful as the CIA has been throughout its history, sometimes 💩 happens to the CIA too. That’ll play a part in the story that I’ll be sharing with you today.

Let’s do this the fun way…Q&A. The floor is now open.

What was the bad thing that happened to you recently?

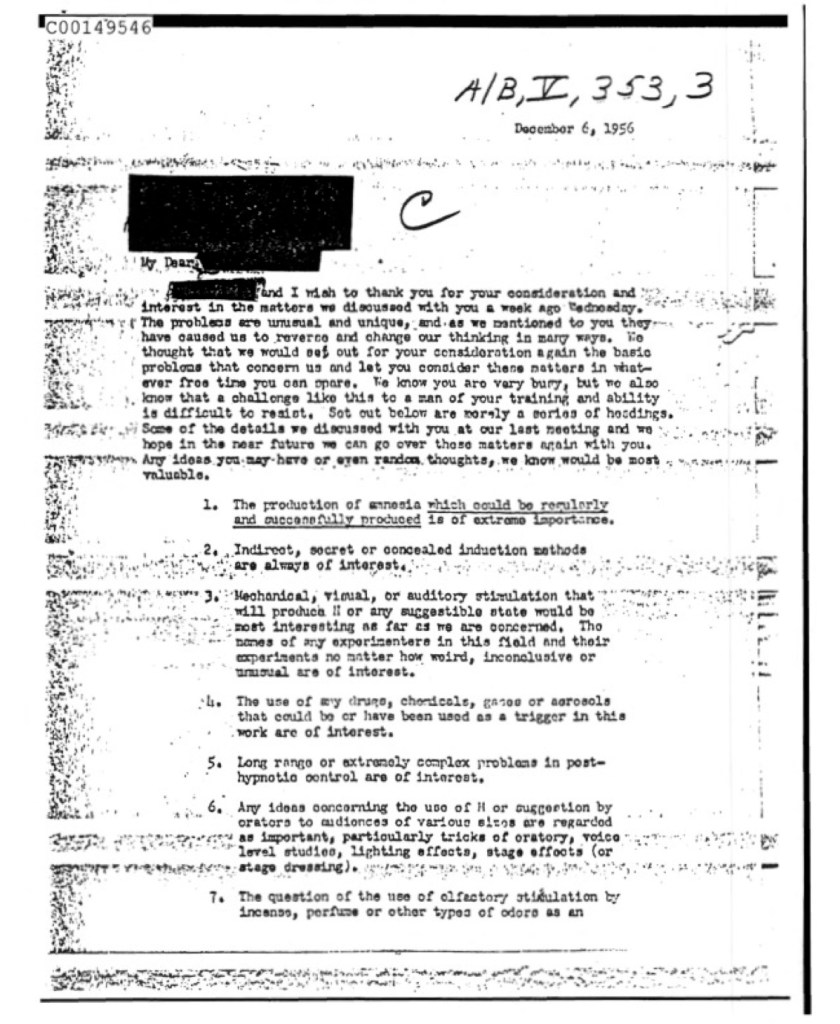

You know my Labor Day post on Facebook? The one where I was discussing a memo that I felt was describing Louis Jolyon West to a “T”? (I still feel that’s the case, by the way.) In my post, I made the bold claim that the number at the top of the memo—A/B, 5, 44/14—was an important clue, and that any document with a similar alphanumeric pattern and a number 44 in the second-to-last position would have something to do with Jolly West. Not only that, but I felt that two memos within that classification were probably describing St. Clair Switzer. Unfortunately, I came to realize later on that I’d gotten some details in my theory wrong, including the part about Switzer.

Of course, I felt horrible because I really hate to say wrong things and mislead you all. But then, after doing a lot more digging, I’ve come to believe that I wasn’t that far off the mark. Yes, some things I got wrong, but I also feel confident that I got a number of things right. So I’m feeling a lot better now.

Here’s a copy of the memo, which was written on April 16, 1954, by the CIA’s Technical Branch chief, Morse Allen, to the chief of the CIA’s Security Research Staff. Paragraph 2 is what convinced me that he was referring to West.

Why are you so sure that April 16, 1954, memo is describing Jolly West?

I’d like to answer your question a little bit now, and a little more later. Based on documents that I found in UCLA’s Archives, West had become disenchanted with his position at Lackland Air Force Base (AFB) not too long after his arrival in July 1952. Back then, he was a 20-something hot-shot psychiatrist and hypnosis researcher who’d performed his residency training in psychiatry at Cornell University’s Payne Whitney Clinic in NYC. West viewed his time at Cornell with fondness, and he’d thought that he might like to return there one day as a faculty member. However, because the Air Force had made it financially possible for him to take his residency training in psychiatry, he was obligated to serve four years at the hospital on base.

In July 1953, when a neurologist who West didn’t seem to care for at Lackland was promoted to supervisor over both the neurology and psychiatry programs, West felt as if his wings had been clipped. He also worried that this development would jeopardize the plans he was cooking up with Sidney Gottlieb in regard to hypnosis and drug research under CIA’s Artichoke program. The last thing he needed was someone looking over his shoulder, especially when that someone wasn’t a believer in the use of hypnosis on patients.

Fast forward to April 1954, when Jolly was being courted by the University of Oklahoma for the position of professor and head of the Department of Psychiatry, Neurology, and Behavioral Sciences. Five days after Morse Allen had written his memo to the chief of the Security Research Staff, the dean of the University of Oklahoma’s School of Medicine wrote to Surgeon General Harry G. Armstrong, asking him to please relieve Jolly West of his duties with the Air Force so they could hire him. Armstrong wasn’t too keen on the idea at first, but by the end of September, under a new surgeon general named Dan Ogle, Jolly was permitted to begin his transition to the University of Oklahoma. It took some fancy finagling by an Agency representative named Major Hughes (I think it was a pseudonym used by Sidney Gottlieb) to help convince Air Force officials that this move would be in everyone’s best interest.

Before we move on, can we talk about the letters and numbers at the top of the memo? What do you think they mean?

Many (though not all) of the MKULTRA documents have similar notations in the upper righthand corner. The A/B is consistently in the front. According to Colin A. Ross, M.D., a psychiatrist, author, and MKULTRA expert, the A/B stands for Artichoke/Bluebird. After the A/B is a number between 1 and 7, which is sometimes written as a Roman numeral. This number represents a grouping of like files. Although I’m not sure about the meaning of the other numbers, the number 5 appears to represent consultants of some sort. The second-to-last number—in this case, 44—is unique to a person or group of people who seem to be linked somehow. The last number is the number assigned to each document within the category. In 44’s case, the last number runs from 1 to 17, with a couple numbers (9 and 11) being skipped over, probably because the CIA decided we shouldn’t see them. One thing I’ve noticed is that the last numbers weren’t assigned in chronological order. Some seem to run in reverse chronological order. This makes me think that they were numbered by someone after MKULTRA became public in 1977.

This question is a two-parter: What was your hypothesis when you wrote your Facebook post on Labor Day and how has that changed?

It has to do with document A/B, 5, 44/1 (aka # 146319), which has the title “RESEARCH PLAN” typed in all caps at the top of the first page. The document describes a research project in which a team of researchers plans to study a demographic group referred to as criminal sexual psychopaths who were being hospitalized in the same facility. The point of the research was to use narco-analysis (psychoanalysis with the assistance of drugs) and hypnosis to see if the patients would admit to actions that they denied but that were documented through police reports and other records. In other words, they wanted to see if they could get people who made a practice of being deceptive to admit the truth.

What I initially thought

First of all, I knew that Jolly West was named in the January 14, 1953, memo as being part of the “well-balanced interrogation research center.” I also knew that Jolly West had written articles on the topic of homosexuality in the Air Force, and had studied airmen who were gay or who were accused of being gay at Lackland AFB from 1952 through 1956. Because it was the 1950s, I’d thought that perhaps it was an archaic term for gay individuals who’d been incarcerated, but I was mistaken. The term “criminal sexual psychopath” generally was used to describe people who’d committed sexual crimes against children and, what’s more, it wasn’t a term that was used universally back then. Canada used it as did the states of Indiana and Michigan. There may have been others, but I wasn’t seeing it in use in Texas or in the military.

I later learned through old news accounts that the study on criminal sexual psychopaths was conducted by Alan Canty, Sr., a psychologist and executive director of the Recorder’s Court Psychopathic Clinic in Detroit, whose work included the analysis and placement of individuals whose cases had gone through the Wayne County criminal justice system. The selected location for the CIA’s project was Ionia State Hospital, in Ionia, Michigan, where 142 individuals labeled as criminal sexual psychopaths had been residing at that time.

What I think now

Because references to Jolly West can be found in documents occupying the same “44” category as the researchers from Michigan, and because the researchers were receiving assistance from at least one outside consultant, my current hypothesis is that West had been providing guidance to them on occasion. Sidney Gottlieb signed off on the Ionia State Hospital project, listed as MKULTRA Subproject 39, on December 9, 1954. By that date, Jolly was spending roughly one week out of every month in his newly acquired academic role in Oklahoma City.

By the by? I still have my suspicions regarding whether Jolly may have been conducting his own studies on gay airmen stationed at Lackland AFB. In 1953, Air Force Regulation (AFR) 35-66 mandated that homosexuals were not permitted in the Air Force. If someone was caught in the act or if someone reported their suspicions to the authorities, that person would be subjected to a lengthy investigation, a portion of which included a psychiatric examination, which is when Jolly West would enter the picture. What’s more, during the investigative period, these men were placed on “casual status,” and relocated to a special barracks to await the results of their respective investigations and final rulings, a process which could take months. Somehow, I can’t imagine West walking by the special barracks and not thinking that these men sequestered together with little else to do would make good test subjects in the detection of deception.

Now that we know what the criminal sexual psychopath study was about, can I address the rest of the question that you’d asked earlier about how I’m sure that the April 1954 memo is referring to Jolly West?

Yeah, sure. Why else do you think the April 1954 memo is referring to Jolly West?

I’ve researched the primary participants in the criminal sexual psychopath study, and everyone was steadfastly employed in their positions in April 1954. Ostensibly, no one was looking for work elsewhere as evidenced by the fact that no one left. In addition, a psychiatrist and an anesthesiologist from the University of Minnesota whom I suspected had offered guidance to the Michiganders were happy in their jobs as well. To the best of my knowledge, no one directly or peripherally tied to that project was being considered for another job in April 1954. Only Louis Jolyon West.

Interesting. I noticed that you said there were ‘references’—plural—to Jolly West in documents occupying the same ‘44’ category as the researchers from Michigan. Where else have you found a reference to West?

Excellent catch! This is where our story gets fun…and it’s also where, as I noted earlier, the CIA was experiencing some, um, difficulty of the “💩’s a-happenin’” variety.

It all began when I was using the searchable, sortable MKULTRA index that Good Man friend and history buff Julie Miles created, and focusing heavily on the documents that were dated within the window of 1952 through 1954. I noticed that, at some point, a psychiatrist was having a tough time getting through the CIA’s clearance process. I’ve read that CIA clearance is a lengthy process that’s stricter than any of the other federal agencies, so it didn’t surprise me that it wouldn’t be easy. Fleetingly, I may have wondered who it might have been, but I didn’t get all that hung up over it.

Then I read document A/B, 5, 44/3 (#146321), dated July 24, 1953. The document is a memo from Morse Allen, chief of the Technical Branch, to the chief of the Security Research Staff, and he’s seriously worked up over the clearance issue.

Apparently, when the CIA’s Special Security Division (SSD) was conducting its preliminary investigation into Morse’s man of interest, they discovered that another entity had conducted an investigation into that same person in mid-June 1953.

The other investigation was described as a “full field investigation,” which is an intensive background check into new government hires in which interviews are conducted with former bosses, family members, neighbors, clergy, you name it, and their comments are written up into summaries called “synopses.” Although full field investigations had been used before in the federal government, they were more notably implemented after Exec. Order 10450 was signed in April 1953. At that point, all civilian federal agencies were required to conduct full field investigations on new hires to make sure they wouldn’t be putting the nation at risk by giving information to the communists. The military required a full field investigation for Top Secret classifications. (As you may recall, the real reason behind Exec. Order 10450 was to purge the federal government of homosexuals because they claimed that they could be blackmailed.)

So, to quickly recap: someone other than the CIA had conducted a full field investigation on Morse Allen’s man of interest and the memo which discusses the findings is labeled under the #44 category.

Moreover, this particular full field investigation had something to do with the military. I believe this is true because, over New Year’s this year, this blog site took advantage of the down time to decode what some of the letters in the margins of the MKULTRA documents mean. For example, we determined that an “A” stands for an Agency employee; a “C” stands for a contractor; and so on. (They didn’t always start with the same letter, but in those cases, they did.) In the July 24, 1953, document, the margins are filled with A’s, C’s, and H’s, the latter of which, we determined, was used for the Department of Defense or one of its military branches.

That’s extremely interesting, because none of the other people associated with the proposed research project at Ionia State Hospital had anything to do with the military. They would have needed to undergo the CIA’s clearance process, but they wouldn’t have to be subjected to a full field investigation by the military in June 1953.

There’s a lot in this memo, which we can discuss in the comments if you’d like. For now, let’s go to my favorite paragraph, which is paragraph number 5:

“You will note that these synopses indicate that REDACTED is ‘talkative,’ somewhat ‘unconventional’ and a ‘champion of the underdog’ but, according to all informants, he does not discuss classified information and can be trusted with Top Secret matters.”

That’s it. That’s the giveaway. Morse Allen is talking about Louis Jolyon West.

Wait—why is that the giveaway? Was Jolly West talkative? Unconventional? Was he a champion of the underdog?

The answers are yes, yes, and, although you may find this surprising, yes he was. But don’t take my word for it. I have a few anecdotes to share.

On being talkative

First, there was his nickname—Jolly West—which is an indicator of his gigantic personality that seemed to match his size 2XL frame. A 1985 Los Angeles Times article on Jolly and his wife Kathryn said: “Psychiatrist West’s nickname, Jolly, seems unlikely to casual acquaintances, for his manner is serious, attentive, concerned. But he lightens up with frequent moments of laughter, and he can convey a measure of humor even in moments of stress.”

That was written when Jolly was a mellow 61. Imagine him when he was 28 and eager to impress his superiors and overpower his competition.

In an article that appeared in the U.K. publication The Independent after his death, a colleague of West’s, Dr. Milton H. Miller, said he was: “above all, a colourful figure, an alive person who loved to be on stage.”

On being unconventional

This is a broad term—what does it even mean? But yes, it’s safe to say that Jolly West wasn’t your run-of-the-mill psychiatrist who’d been sent to medical school by monied parents. His father had immigrated to the United States from Ukraine, and according to The Independent, his mother taught piano lessons in Brooklyn. His family, who’d later moved to Madison, WI, struggled financially, and he had to work hard and think creatively to find his way in the world.

“We were, in fact, quite poor,” West said in the 1985 L.A. Times article. “Some of our neighbors didn’t have jobs. Some had no books. The family across the street had no bathtub. It was strictly the wrong side of the tracks. But in our house there was an attitude of ‘Thank God, we’re in America,’ and there was always a willingness to help others.”

According to that same article, West enlisted in the Army during WWII because, as a Jewish teen, he took Hitler’s fascism personally and he wanted to fight and kill.

“I was a bloodthirsty young fellow,” he said.

Because there was a shortage of Army physicians, the Army steered Jolly West to medical school, first at the University of Iowa, and later at the University of Minnesota. As mentioned earlier, the Air Force had financially supported his residency at Cornell, which is why he was obligated to serve at Lackland AFB for four years before finally severing his military ties.

On being a champion of the underdog

This one is so fascinating, knowing what we now know about West and some of his more questionable actions during the MKULTRA years. But he truly was a believer in civil rights.

A 2001 article on Charlton Heston in the Los Angeles Magazine said that Heston and Louis Jolyon West were best friends(!) and that in the 1950s, after Jolly had moved to the University of Oklahoma, he’d reached out to Heston, and “the two friends teamed up with a black colleague of West’s to desegregate local lunch counters.”

In 1983 and 1984, Jolly flew to South Africa to speak out against apartheid.

“Everybody makes a difference,” he said in the 1985 L.A. Times article. “You can fight city hall. You can change the world. It might not seem like much of a change at the time, but you have the power as an individual to do a great deal.”

West was also fiercely opposed to capital punishment. In 1975, he published a paper in the American Journal of Orthopsychiatry which provided one of the most strongly-worded abstracts I’ve ever read—and I’ve read a lot of them:

“Capital punishment is outdated, immoral, wasteful, cruel, brutalizing, unfair, irrevocable, useless, dangerous, and obstructive of justice. In addition, psychiatric observations reveal that it generates disease through the torture of death row; it perverts the identity of physicians from trials to prison wards to executions; and, paradoxically, it breeds more murder than it deters.”

So, yeah. I can see someone describing Jolly West with the words used in the memo. That the CIA would consider someone being characterized as a “champion of the underdog” as a knock against him kind of tells you all you need to know about the CIA of the 1950s.`

But what about the last part of paragraph 5? The part that said: “according to all informants, he does not discuss classified information and can be trusted with Top Secret matters.” Under what scenario would Jolly West come into contact with “informants”—again, plural—and be in a position to discuss classified information with them?

That line threw me too until I thought about the people West associated with when he was at Cornell. Two of the faculty members that he would have known well were Harold G. Wolff, a personal friend of Allen Dulles, and Lawrence E. Hinkle, who published a study with Wolff titled “Communist Interrogation and Indoctrination of ‘Enemies of the State’” in 1956. They were the CIA’s go-to’s in brainwashing.

In 1955, Wolff created the Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology (later referred to as the Human Ecology Fund), which supported the Ionia State Hospital study. Hinkle, who was also in a leadership role in the society, was one of the primary contacts for the study’s researchers. It’s certainly plausible that Harold Wolff, Lawrence Hinkle, and Jolly West could have discussed national secrets when Jolly was conducting hypnosis studies at Cornell. For Morse Allen to identify Hinkle and Wolff as CIA informants in July 1953 doesn’t seem like a stretch of the imagination. Not in the least.

Oh my gosh. I just thought of something.

What?

Read Paragraph 6 of the July 24, 1953, memo. Morse Allen says the following:

“In further consideration, it should be remembered that REDACTED will be dealing with close personal friends and close professional associates of his in the REDACTED ARTICHOKE work and further if he works with us his professional reputation may conceivably be greatly enhanced by successful development of our program. These elements should be weighed, of course, in the evaluation of REDACTED.”

When you consider paragraphs 5 and 6 together, Morse Allen is saying: yes, I agree, West is currently an immature idealist. But if he could be cleared according to our plan—which is at the Secret level, not even Top Secret—he’ll be in close contact with CIA-sanctioned researchers Harold Wolff and Lawrence Hinkle, which will “greatly enhance” his “professional reputation.” In other words, if Security would just clear him, Morse and his pals could mold Jolly West into the person they desire him to be. Less angry young man—more “this is the way the world works.” Because Wolff and Hinkle were closely tied to the Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology, and the society funded the Ionia State Hospital study, it’s conceivable that Louis Jolyon West played a role in the study too, which was good reason to have his documents marked with a “44.”

[You can link to the 1957 Annual Report of the Society for the Investigation of Human Ecology.]

Very interesting. But how does that impact your hypothesis regarding St. Clair Switzer?

I’m happy you brought this up. You’re absolutely right—that’s why we’re here. We’re trying to understand how Ronald Tammen’s psychology professor St. Clair Switzer might have been used in Project Artichoke and, in turn, what might have happened to Ronald Tammen after he went missing from Miami University’s campus.

I haven’t budged from my belief that, in January 1953, St. Clair Switzer was mentioned in the same paragraph as Louis J. West for a “well-balanced interrogation research center.” In fact, I feel stronger about that hypothesis now more than ever.

Let’s zoom in on the names of the Major and the Lt. Colonel in paragraph 3 of the January 14 memo. When we zoom in on the Major, we can see the letters of West’s first name—the L, the o, the u, the dotted i, and the s—even though it’s crossed out. We can see the J. We can sort of see the West. It’s him. Also, we know that Sidney Gottlieb was having conversations with West about a hypnosis and drug research center in June and early July 1953—roughly the time when the CIA’s Security office was conducting its preliminary investigation into the person who was talkative and unconventional.

The Lt. Colonel’s name is harder to see, but I definitely see a capital S. Without a doubt. I happen to see a w and a z as well. (Oh, who am I kidding? I see all the letters.) And I’ll be honest—I haven’t come across very many lieutenant colonels in the Air Force in 1953 with last names that began with S that were also hypnosis experts. In fact, I only know of one. (Switzer.) We’re still waiting on our Mandatory Declassification Review to see if we can finally remove the redactions and put that question to rest.

But there’s more. Do you recall how, at first, the Air Force Surgeon General’s Office wasn’t entirely on board with having the CIA using one of its bases as a testing ground for hypnosis and drugs? A memo dated September 23, 1952, was focused upon two individuals who were under consideration for the endeavor. Person A, a U.S. commander, had “nothing to contribute in the line of research.” (See paragraph 2.)

As for Person B, a CIA rep said they were “inclined to go easy on him from a security standpoint, because of his propensity to talk.” (See paragraph 3.)

In paragraph 4, a colonel in the Surgeon General’s Office was speaking of Person A (I believe) when he said that “he thinks very highly of REDACTED, and that it will be essential to keep him cut into the picture.” The words “air research” were handwritten above the essential person’s blackened name.

In a former blog post, I argued that Person A, the one whom the colonel thought very highly of, was likely St. Clair Switzer, since he’d recently spent a summer working for the Air Research and Development Command, and he and the surgeon general had a connection with Wright Patterson AFB. Perhaps Switzer’s name was being floated as a liaison between the interrogation research center at Lackland AFB and the Office of the Surgeon General.

Today, I’m adding to that hypothesis. I’d suggest that Person B, who had the “propensity to talk,” was Jolly West. Perhaps the Office of the Surgeon General thought West a wee bit too chatty, and St. Clair Switzer—quiet, conventional, obsequious to the powerful—was brought in to appease the brass.

OK! I think that’s all for today. Questions? Concerns?

**********************

To demonstrate how well Jolly West knew the guys at Cornell, he’s written Dr. Harold G. Wolff’s name as a character reference on a form he’d filled out on November 4, 1955. (I don’t know the purpose of the form.) Wolff’s name is directly below West’s adviser at Cornell, Dr. Oskar Diethelm.