What’s more, I think Sidney Gottlieb (or someone who worked for him) was on Miami’s campus in September 1952

Remember the game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon”? (If you don’t, you can read about it here.) Back in the 90s, my brother and his partner, who live in NYC, had two Akitas named Oscar and Chanel. Oscar was the smaller of the two, a chocolaty brown color, while Chanel was big and white, a chaise lounge on four furry legs. They were sweet, mellow doggies. When they went out on their walks, everyone knew them by name. “Hi Oscar! Hi Chanel!” people would say to them, and Oscar and Chanel would say hi back in their sweet, mellow way. Two of the people who used to say hello to them on a regular basis were Kevin Bacon and Kyra Sedgwick. No lie. According to the game, that would make Oscar and Chanel one degree of separation from Kevin Bacon. And because I, too, was a friend of Oscar and Chanel’s, that would make me two degrees of separation from Kevin Bacon, which, to this day, is something I’m enormously proud of. I can’t believe we haven’t talked about this before.

So, what if we were to play the same game with the father of MKULTRA, Sidney Gottlieb? Most people would hope for as many degrees of separation as possible from that guy. And in 1953, anything fewer than 10 degrees would be much, much too close. But, as I’ll be showing you today, St. Clair Switzer was, I strongly believe, one degree of separation from Dr. Gottlieb, which means that he knew the man. And because Ronald Tammen knew St. Clair Switzer, that would place Ron at two degrees of separation from Sidney Gottlieb, which, in 1953, is uncomfortably close for anyone, let alone a vulnerable college student who respected persons of authority. And that’s presuming that they didn’t meet. There’s a chance that Ronald Tammen and Sidney Gottlieb actually did meet.

I have a lot of info to share, and not much time today in which to write it all down. Let’s do it this way. I’ll be posting several documents that explain why I believe St. Clair Switzer was of vital importance to the CIA in the days of MKULTRA. I’ll also be showing you how Sidney Gottlieb and St. Clair Switzer likely came into contact with one another as well as the actual date when I believe Sidney Gottlieb or one of his associates paid a visit to Switzer in Oxford, Ohio. For each case, first I’ll post the document, and below that, I’ll include a brief narrative regarding why I think it’s important, pointing out some of the can’t-miss parts. Of course, the documents are heavily redacted—you won’t see anyone’s name except for Sidney Gottlieb’s—but that doesn’t mean they don’t have their clues.

Sound fun? Let’s go!

Setting the stage

As we discussed in my last blog post, someone whose writing style had a Switzer-y ring to it had written a report for the Psychology Strategy Board (PSB), a high-level group of military and intelligence officials who oversaw the military’s psychological operations. The report was a thorough review of Artichoke-related research findings to date with extensive bibliographies for each chapter, except for two. For some reason, the researcher’s thoughts on lobotomy and electric shock and memory had no bibliography. The report was dated September 5, 1952, which happened to be exactly two weeks to the day before the start of the fall semester at Miami University.

At the time of the PSB report, the CIA had been seeking guidance from the Department of Defense’s (DoD’s) Research and Development Board (RDB) regarding the feasibility of using hypnosis, drugs, and other mind-altering methods as part of the process of interrogating prisoners of war. Because the PSB membership had many of the same people as the CIA and DoD, someone in that group likely figured that the PSB could lend a hand in providing a literature review, which is how I believe the PSB report and its accompanying bibliographies came to be.

In the blog, I argue that St. Clair Switzer was indeed the report’s author, since he was in the perfect place in which to write it—Dayton, Ohio, home of the Armed Services Technical Information Agency, or ASTIA, which contained all of the technical studies funded by every branch of the U.S. military. In addition, Switzer was supremely qualified to conduct such a study. His name had recently been given to Commander Robert J. Williams, of the CIA’s Office of Scientific Intelligence, who at that time was the project coordinator of Artichoke. Switzer was an Air Force lieutenant colonel who had studied under the eminent psychologist and hypnosis expert Clark Hull and who had earned a pharmacy degree to boot. Switzer had another connection. Sidney Souers, adviser to President Truman and the creator of the PSB, was a Dayton native and Miami University graduate. Needless to say, the PSB study was well-received by both the military and intelligence people. Switzer’s report and its accompanying bibliographies were in high demand.

Therefore, in the fall of 1952, I’m guessing that St. Clair Switzer was feeling rather full of himself. People who held our nation’s most sensitive jobs were clambering for his report. From what I can tell, they were even referring to the report by his name—the Switzer Report.

September 23, 1952

This memorandum describes a couple conversations that had taken place concerning Artichoke on September 22 and 23, 1952, a Monday and Tuesday. In the first paragraph, the writer is discussing the transition that’s been in the works for a while. The oversight of Project Artichoke had been passed from the Office of Scientific Intelligence (OSI) to the Inspection and Security Office (I&SO, or just plain OS), and therefore, a couple staffers were planning to spend some time in OS on the 24th to help them process files. They also said they’d keep an eye out for anything that might be of interest to OTS, which stands for the Office of Technical Service, the office that was now responsible for overseeing Artichoke research. Even though OTS was headed by Willis Gibbons, the office’s point person on Project Artichoke was Sidney Gottlieb, who ran OTS’s Chemical Division. When MKULTRA officially kicked off on April 13, 1953, Gottlieb would be put in charge. However, according to Poisoner in Chief author Stephen Kinzer, even though Gibbons was Gottlieb’s boss on paper, Gottlieb answered to Richard Helms, who was the chief of operations in the Directorate of Plans, the extremely powerful group that directed all of the CIA’s covert activities. When you see an OTS in these memos, think of Sidney Gottlieb, since he was running the show in the area of Artichoke research.

It’s paragraphs 2, 3, and 4, that interest me the most, especially 2 and 4. In paragraph 2, the writer is discussing a person whose name is crossed out, above which I believe someone has written “U.S. commander.” Here’s the full paragraph:

On the subject of Dr. REDACTED, REDACTED thinks that the consensus is that he has nothing to contribute in the line of research. I asked him whether Dr. REDACTED might not have been exploring this further on the occasion of his 19 September visit and, although Mr. REDACTED does not believe this to be the case, he will check with OTS.

Here’s why I think they’re talking about Doc Switzer:

- Switzer had just produced a noteworthy document for the CIA and military, and his background would have seemed a perfect fit for Project Artichoke. It would be normal for them to wonder if they could continue using his services in some way.

- In the Air Force, the term “U.S. commander” can be translated to lieutenant colonel, which is Switzer’s rank. If you’re wondering if they could have been discussing Commander R.J. Williams, we know that they aren’t, since Williams was neither an M.D. nor a Ph.D.

- It’s true that Doc Switzer didn’t have the same research capabilities as, say, a Louis Jolyon West, who’d moved to Lackland Air Force Base, in San Antonio, in July 1952. West had access to a laboratory and other facilities for conducting the sort of testing that the CIA was interested in, whereas Doc Switzer’s role at Miami University was that of a professor.

- On the date of September 19, 1952, a Friday, someone associated with OTS had visited with the person they’re discussing. The writer asks if perhaps they were exploring the person’s research capabilities, and the other person said they’d check with OTS.

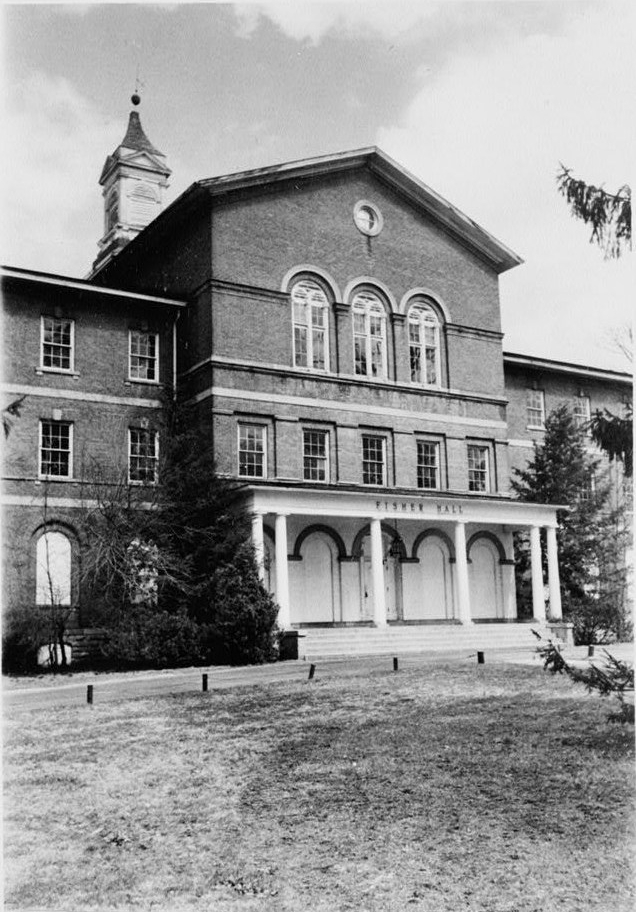

As I’ve mentioned, September 19, 1952, was the first day of classes at Miami University. Oddly enough, a few days prior to that, several men were reportedly on the front porch of Fisher Hall recruiting students for a hypnosis study through the Psychology Department. Could someone from OTS—possibly Sidney Gottlieb himself—have notified Dr. Switzer that he would be paying a visit, and in preparation, people affiliated with the Psychology Department were rounding up volunteers for the OTS representative’s visit? I mean…it’s possible, right?

Paragraph 3 is harder to discern. The writer is discussing the Surgeon General’s Office. You may not know this (I certainly didn’t) but each branch of the military (Army, Navy, and Air Force) has its own Surgeon General in addition to the “main” Surgeon General, which is the Surgeon General of the U. S. Public Health Service. Because of documents that I’ll be providing momentarily, I believe they were referring to the Surgeon General of the Air Force. The CIA writer in the Office of Security is discussing working with them, and he also said that they plan to go easy on someone’s security clearance because they’re a talker, which doesn’t sound like Switzer at all. I’m still trying to figure out this paragraph and whether it’s relevant. Let’s skip it for now and move on to the fun stuff.

Paragraph 4 seems more clear, especially in light of the January 14, 1953, memo below. As luck would have it, the person who would have had to give his OK to interrogation research on an Air Force Base was a guy by the name of A. Pharo Gagge. (The A stood for Adolph. I’m sure you can understand why a WWII officer would avoid using it.) Before he was in his position as chief of the Human Factors Division in the USAF Directorate of Research and Development, he was chief of the Medical Research Division of the Surgeon General’s Office, and before that, he was director of research and acting chief of the Aero Medical Laboratory at Wright Patterson Air Force Base in Dayton, Ohio. He was born in Columbus, Ohio. Without question, he would have known Doc Switzer.

It makes sense that the CIA would refer to anyone in the Directorate of Research and Development as being part of the Surgeon General’s Office, since the directorate was directly overseen by the Surgeon General’s Office. In addition, A. Pharo Gagge was a Ph.D. and a colonel. Here’s the paragraph that I adore:

On 23 September, Col. REDACTED called to say that he had talked to Col. REDACTED of the Surgeon General’s Office and that REDACTED had advised him that he thinks very highly of REDACTED and that it will be essential to keep him cut into the picture. I advised REDACTED of my conversation with Mr. REDACTED and of the procedure outlined by him. Col. REDACTED is very pleased with this arrangement and considers that this coordination will give him maximum CIA support.

Here’s why I think they’re talking about Switzer again:

- From what I can tell, there’s only one person in this memo that the CIA was considering dropping, and that person was the man in paragraph #2, the person I believe to be St. Clair Switzer. And if it is indeed Switzer that they were considering not using further, someone in the Surgeon General’s Office put an end to that talk. The word they used was essential—as in, it would be “essential to keep him cut into the picture.” After the writer seemed to assuage the colonel’s concerns, he was “very pleased,” and the CIA was that much closer to moving forward on their project.

- Above the person’s scratched-out name on line three of the fourth paragraph, it appears as though someone has written the word “research.” I can see Pharo agreeing to the use of Switzer in this capacity—the book kind of research, versus the laboratory kind—which is an idea that was reinforced later on.

January 14, 1953, page 1

You’ve seen this memo already—I’ve referred to it many times. It’s the one where, in the third paragraph, they’re seeking three people, two of whom are named, for a “well-balanced interrogation research center.”

The first person, Major REDACTED, USAF (MC), is Louis J. West, without question. If you zoom in on the paragraph, you can actually see the word Louis at the front of his name, and you can make out other key letters too. They describe him as being “a trained hypnotist,” which is a colossal understatement. He was chief of the Psychiatric Division at Lackland Air Force Base in San Antonio. Maybe the writer of the memo figured his audience already knew that part?

The second person, who is not named, is described as “another man well grounded in conventional psychological interrogation and polygraph techniques.”

And the third person, Lt. Col. REDACTED, isn’t described at all. The only thing they say is that they’re hoping that “the services of Lt. Col. REDACTED” can be obtained, along with the other two men, for their well-balanced interrogation research center.

So this fits too. Lt. Col. Switzer’s name would be there because A. Pharo Gagge wanted it there. They don’t specify the services he’d provide because they’re leaving the possibilities open. I probably would have called him a liaison/researcher. You’ll see why in a second.

March 5, 1953

The last memo I’m sharing with you has to do with one of the regularly scheduled Artichoke meetings—this one having occurred on February 19, 1953. For some reason, the only participant whose name isn’t redacted is Sidney Gottlieb, representing OTS. (Many thanks to the redactionist for this act of kindness!)

Because these minutes cover a lot of territory, we’re only going to concentrate on two sections. The memo is also difficult to read, so I’ve typed a transcript of the entire document in case you’re interested.

First is section 2B., the first paragraph of which reads as follows:

REDACTED pointed out that REDACTED and REDACTED had come aboard and both REDACTED and REDACTED discussed the project at REDACTED involving REDACTED and the using of his facilities for a testing and research ground for our material. It was pointed out that REDACTED was to be our liaison between Headquarters and REDACTED since he knows REDACTED personally and has numerous contacts in the essential city.

The writer is discussing three people, which we’ll call person 1, person 2, and person 3. The first sentence describes persons 1 and 2 coming on board and how they’d be working together on a testing and research ground at someone’s facility “for our material.” (By “material,” I’m pretty sure they mean mind-altering chemicals.) I believe strongly that Louis Jolyon West is person 1 and, based on letters that I have between him and Sidney Gottlieb, the facility they’re speaking about would be at Lackland AFB. As for person 2, I believe that he is Donald W. Hastings, another psychiatrist, who was at the University of Minnesota’s Hospital, and who was very gung ho about the program. I don’t have time to discuss him today, but he’s mentioned in the letters between Jolly West and Sidney Gottlieb, which I’ve included copies of at the end of this post.

Person #3, I believe, is St. Clair Switzer. If I try to fill in the blanks of the second sentence in that paragraph, I believe they’re saying that Switzer was to serve as a liaison between the CIA’s Headquarters and the USAF Surgeon General’s Office since he knows General Gagge personally and has numerous contacts in….Dayton? Could Dayton be the “essential city” because it’s home to Wright Patterson AFB and ASTIA?

Section 2B. continues:

REDACTED pointed out that REDACTED [a consultant] was to be used in a very broad survey of the entire field. He also pointed out that REDACTED was not going to be used specifically to dig into one particular field but would study all ideas across the board and in connection with REDACTED, Dr. Gottlieb and REDACTED would help determine where important lines of interest lie and whether or not discoveries in the scientific and medical field are worthy of our interest, research and study.

The writer appears to be elaborating on Person #3. It’s here that he says that he’ll be used as a consultant to conduct a broad survey of all of the potential areas of interest regarding Project Artichoke. And get a load of who’s going to help him: Sidney Gottlieb plus another person whose name is redacted.

Now let’s jump to section 11, where the group is discussing the Research and Development Board’s Ad Hoc Study Group’s Report. As you’ll recall in my last post, people who were up to their necks in Project Artichoke weren’t enamored with the RDB Report because A. they disagreed with some of the members’ views, and B. it wasn’t focused on the sorts of operational things that they were already doing. Here’s what they had to say:

Following the above, a general discussion was held concerning the RDB Report and the REDACTED Reports. REDACTED pointed out certain differences in the point of view of the members of the Ad Hoc Committee and those engaged in actual operation work. REDACTED stated that the RDB Report was an overall survey of projects going on in the field and was not pointed at the type of work ARTICHOKE is engaged in since this was at the operations level and not in the broad research-experimental field.

Immediately following those comments, the REDACTED Report was brought up—what I believe to be the Switzer Report. Here’s that part of section 11:

During the discussion, REDACTED pointed out to REDACTED and REDACTED that he anticipated receiving from Dr. Gottlieb the bibliography attached to the REDACTED Report soon and he would have it photographed and would turn over a copy to REDACTED for study. Dr. Gottlieb stated he expected the report soon and he would turn it over to REDACTED when he received it. (Bibliography is now being processed.)

So there we have it. Sidney Gottlieb, who was now in charge of all research pertaining to Project Artichoke, had taken a great interest in Doc Switzer’s PSB Report. Surely, he would have followed up with Doc to discuss the report as well as the accompanying bibliographies. And once that door was opened, who knows what other areas of collaboration might have come to pass.

******

As an added bonus, here are the letters between Louis Jolyon West and Sidney Gottlieb, who disguised his name as Sherman Grifford. These letters are part of West’s papers that are held at the UCLA Archives, which I visited a few summers ago. In these letters, West and Gottlieb discuss how to create a research facility at Lackland AFB involving hypnotizing human subjects. At the end of his letter dated July 7, 1953, West adds this:

“It makes me very happy to realize that you can consider me “an asset.” My interest in the entire body of work on which you are engaged is a keen and perhaps even a relatively enlightened one. Any services that I can render, along the lines you have indicated or in any other way, are gladly and eagerly offered. Surely there is no more vital undertaking conceivable in these times.”