After my most recent blog post about when Carl Knox stopped investigating Ron Tammen’s disappearance, a reader and I were discussing the 1976 documentary produced and narrated by Ed Hart of Dayton’s Channel 2. For those people who haven’t watched it yet, I encourage you to do so. It isn’t very long—less than 1/2 hour total. I’ve embedded the two parts on my home page, but you can also link to them here:

The Phantom of Oxford

What’s special about this documentary is that key people tied to the investigation in 1953 have given on-camera interviews in 1976, and what they say is revealing. This got me to thinking that I should transcribe their quotes and post them online. That way we won’t forget the things they said in light of any new information that we’re able to uncover.

As it turns out, creating a transcript of their quotes wasn’t that time-consuming. I recalled that I’d found a transcript of the program in Miami University Archives early in my investigation and had filed it away. I’ll discuss that transcript in more detail a little later, since I believe it reveals something about the person or persons who created it. (Spoiler alert: it wasn’t Ed Hart.)

And so, here you go…the quotes from The Phantom of Oxford along with my thoughts below several of them:

Quotes from The Phantom of Oxford

PART 1

Joe Cella, Hamilton Journal News reporter [0:06]

[Opening]

“I believe Ron Tammen voluntarily walked off campus. I believe he’s somewhere out in the world today…alive, under an assumed name. Everything has been…erased with him…uh…and I believe he’s still out there.”

Oh, man, me too, Joe, with one slight difference: I think Ron was driven off campus. But other than that, I totally agree with you, 100 percent, that Ron Tammen was still very much alive in 1976.

Charles Findlay, Ron Tammen’s roommate [5:40]

[Describing his return to his and Ron’s room in Fisher Hall on Sunday night, April 19, 1953]

“I came back to campus, to Fisher Hall, and went to my room as normal and the light was on in the room. And in the room, the door was unlocked, and Ron’s book was open on his side of the desk. And uh…the desk chair was pulled back as though he got up and went somewhere. So I thought not too much about that and I studied I think till eleven o’clock that night. I got back to school about nine o’clock, went to bed as usual, and got up the next morning and didn’t see Ron in his bed. I still wasn’t too excited about it because I thought he might have spent the night at the fraternity house.”

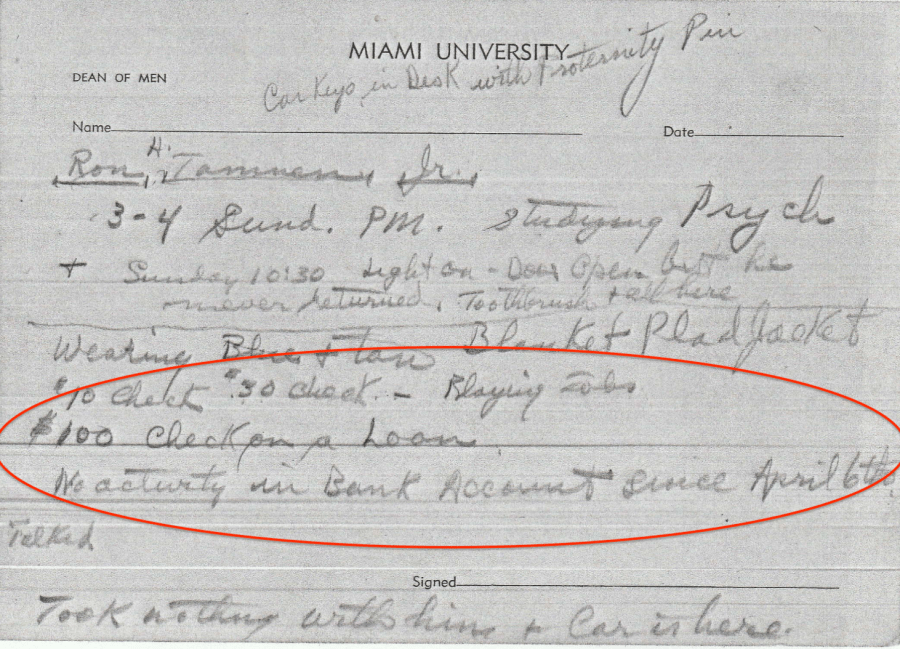

For the life of this blog, I’ve been reporting that Chuck had arrived back at Fisher Hall at around 10:30 p.m. I’ve reported that time because A) that was the time reported by Joe Cella in his one-year anniversary article in the Hamilton Journal News on April 22, 1954, and B) Carl Knox had written the time 10:30 on one of his note pages along with the words “Light on – Door open but he never returned.” Carl didn’t say what happened at 10:30, but I presumed that’s when Chuck had arrived at the room, as corroborated by Cella. I’m now wondering about that time. This has nothing to do with Cella, by the way, who was an excellent reporter. But it might have something to do with what someone had told Cella when he was writing his one-year anniversary article.

In the video, Chuck says that he returned to Miami at 9 p.m. I figured that, with 23 years having transpired since he’d recounted the story, that detail may have become a little fuzzy. However, when I went back to read the earliest news articles, I found this in the April 28, 1953, Miami Student, which was overseen by journalism professor Gilson Wright, who also reported on the case: “Tammen, a counselor in Fisher Hall, disappeared sometime between 8 and 9 on a Sunday night.” How do they know it was before 9 p.m.? It may just be sloppy reporting, but could Chuck Findlay have arrived at 9, which is how they would have been able to provide that timestamp? And if that’s the case, what would the 10:30 signify in Carl Knox’s note? Of course, it may indeed be the time of Chuck’s arrival, but what if it was something else—such as the time Ron had walked back to the dorms with Paul (not his real name) and Chip Anderson or the time someone may have spotted Ron sitting in a car with a woman before driving off? Something to ponder…

Addendum: I’ve added Carl Knox’s note to the bottom of this post.

Charles Findlay [6:36]

[Describing the next day, Monday, April 20…]

“And it was sometime later that afternoon, the evening, we had a counselors meeting. And that’s when I think we discussed a little more, a little further, as to what, where Ron was and what the situation was.”

Charles Findlay [7:40]

[Describing when it first hit him that Ron probably wasn’t coming back]

“I think probably the first three or four days I wasn’t concerned. But I really realized he wasn’t coming back, he wasn’t coming back as he normally would, when the ROTC was out and they were dragging the pond, I get concerned. Cause I remember sitting at my desk and looking out the window and watching them drag the pond…and that was kind of an eerie feeling.”

Ed Hart: Someone must have thought that there was foul play involved. Did you?

“No, I didn’t. I didn’t think so because at that time, even now, you go back and you think about a college student, what 19, 20 years of age. How do you make an enemy? And who would think that a college student would have much money?”

As we’ve discussed in the past, if Ron was gay, then there was a chance that he could have been the victim of a hate crime. However, because we now have evidence that the FBI expunged Ron’s fingerprints in 2002 due to the Privacy Act, that tells us that Ron was still alive in 2002. (Per the FBI: only the subject of the record can request an expungement of that record.) Therefore, I don’t believe Ron was a victim of foul play.

Jim Larkins, fellow sophomore counselor in Fisher Hall [8:40]

[Describing why he felt it didn’t make sense for Ron to run away]

“He is just the last person that you would ever expect just to merely take off uh… for as far as I was concerned there would be no reason for his having done it. From all that we could…all that we knew about him and could learn about him he just seemed to have everything going for him.”

Carl Knox, dean of men at Miami University, who oversaw the university’s investigation into Ron’s disappearance [9:33]

[Describing students in the 1950s and a little about Ron as a person]

“Much more it was known as the apathetic period of time. It was certainly uh…far different from the Sixties but uh…it was generally a fairly happy time, sort of normal activities taking place. This young man was uh…well appreciated around campus because of his musical talent. He played bass with the Campus Owls uh…he did and was one of few people on campus who had a car permit in order to transport that bass viol around. And one of the oddities of the thing because he prized it so highly was the fact his car was found locked up with the bass inside and uh…no Ron.”

In his role as the dean of men, Carl Knox was responsible for all male students on campus. He made a point of knowing the students, especially the ones who were most active. I’ve been told that he likely knew Ron Tammen, though probably not very well. H.H. Stephenson, who was an employee of Carl’s, would have known Ron a lot better. We’ll get to H.H. in a minute.

Ronald Tammen, Sr., Ron’s father [10:52]

[Describing his perceptions of the last time he saw Ron, who’d been in Cleveland playing with the Campus Owls the weekend before he disappeared]

“He just seemed to have fun the whole time he was there. There was never anything at all that would indicate there was a (laugh) he had a problem or a thing was bothering him. Nothing at all.”

That’s how Ron’s father may have perceived his son, but there was obviously a lot more going on inside that “fun” veneer. If something was bothering Ron, especially if he was dealing with the sorts of stresses that I think he was dealing with—his grades, his finances, his sexuality—I doubt that he would have gone to his father, who was known to be decidedly not fun in certain situations.

Joe Cella [11:25]

[Describing his impression of how the investigation into Ron’s disappearance was conducted]

“I wasn’t too keen on the initial investigation that went on. It was very abruptly done. To me there was no thorough investigation. And that’s the reason I stayed with it. Over a period uh…of years that followed, we were able to accumulate a lot more, much more, than we ever had initially.”

THANK YOU, Joe, for sticking with it! It’s because of the leads you chased down that we’ve been able to get to the place we are now.

PART 2

Dr. Garret Boone, physician and Butler County coroner [0:16]

[Describing his experience when he tried to notify Miami officials at that time about Ron’s visit to his office in November 1952 to have his blood type tested]

“On one occasion…uh…led to some uh…sharp words between a…uh…between me and two Miami University personnel who did not appreciate uh…my uh…being concerned about the problem of his disappearance.”

Ed Hart: Why?

“Well, I really don’t know. Uh…they might have been bored with me and maybe they got fed…been fed up by reporters and TV men, I’m not sure…which.”

Wouldn’t you love to know who the two Miami personnel were? Doc Boone may have given us a couple clues. What I’m getting from his comment is A) he went to the university in person, since he was ostensibly talking with two people at the same time; and B) the personnel seemed to be the types of people who frequently dealt with “reporters and TV men.” Therefore, it sounds as if one of the two persons handled media relations. Was the other person Carl Knox? It’s my understanding that he was a soft-spoken man who employed a velvet-hammer type of leadership style. For this reason, it’s difficult to imagine him engaging in “sharp words” with a public official who was offering to lend his assistance in the investigation.

Ronald Tammen, Sr. [1:20]

[Describing his impressions of the investigation]

“I was happy that we got the FBI to be involved because of the broad coverage. But uh…I can’t say that I’ve ever been happy about anything that’s happened in the case, because nothing’s ever happened.”

Ronald Tammen, Sr. [1:51]

[Describing the effect Ron’s disappearance had on Mrs. Tammen]

“So much with the wife that uh…big problems occurred with her health. It was just beyond her…she just couldn’t take care uh she couldn’t take it and her health started failing and that was…that was the cause, I believe, of her death was his disappearance and no evidence or solutions at any time.”

This is probably Mr. Tammen’s most revealing statement. First, he refers to Mrs. Tammen as “the wife,” which is about as impersonal as he could be. Maybe it was how they talked in the 1950s, but in the ’70s? I’d think he could have spoken more affectionately…how about “my wife,” or “Ron’s mother,” or, best of all, “Marjorie”?

Mr. Tammen’s biggest slip was when he said “she just couldn’t take care uh she couldn’t take it.” As we’ve discussed, Marjorie was an alcoholic for years before Ron disappeared. As you can imagine, his disappearance didn’t help in that regard. When Mr. Tammen said she “couldn’t take care,” I believe he was about to give away too much information about her condition. Was he going to say that she couldn’t take care of herself? Their two younger children, Robert and Marcia? I don’t know. But he caught himself just in time.

Carl Knox [2:40]

[Describing why Ron’s disappearance had stood out for him throughout his career]

“On other campuses where I’ve been located there have been disappearances and there have been tragedies, but nothing which has sort of popped out of…

No background of explanation, no way of reasonable…uh anticipation, but just suddenly happening and there you were with uh…uh…egg on your face, deepfelt concerns and yet uh…no answers for any part of it.”

Ed Hart: And yet something tells you Ron Tammen is alive?

“Yes, I feel this. I feel it…keenly.”

I believe Carl Knox had discovered information about Tammen’s life and disappearance that he was not making public, likely after having been told by someone in a position of authority. Remember how he’d had a buzzer installed on his secretary’s desk for Tammen-related calls? Or how his secretary was given a list of words that she was instructed not to say to reporters? And we’ve since learned that he’d discovered that Dorothy Craig of Champion Paper and Fibre had written a check to Ron shortly before he disappeared. When asked 23 years later if Ron Tammen was alive, he said, “Yes, I feel this. I feel it…keenly.” This tells me that Carl had some indication that Ron was in ostensibly trustworthy hands when he left Miami’s campus. Like the U.S. government’s perhaps?

Barbara Spivey Jewell, daughter of Clara Spivey, who was at her mother’s house in Seven Mile, Ohio, when a young man who looked like Tammen showed up late at night on Sunday, April 19, 1953 [3:33]

[Describing when her mother and she notified the Oxford police about the young man’s visit]

“Well, we saw his picture in the paper about a week afterwards and my mother said, well that’s the boy that was here at our door. And so we went to Oxford to the police station and talked to them. But uh…I was at the door with my mother also and I’m um…positive it was him.”

It was actually two months later, not a week. Also, a third person in the room, Barbara’s eventual second husband, Paul Jewell, told Detective Frank Smith in 2008-ish that he was “absolutely confident” it wasn’t Ron. He thought it was a local ruffian.

Barbara Spivey Jewell [4:07]

[Describing whether she’s still convinced that it was Ron]

“I would still say that it was him. I’m positive. I can still see his dark eyes and his dark hair.”

H.H. Stephenson, Miami housing official who saw a young man who looked like Ron dining in Wellsville, NY, on August 5, 1953 [4:44]

[Describing his experience in the Wellsville, NY, restaurant]

“When my eyes would look toward him I would find he was looking at me. And I had that feeling that uh… that he was sort of looking right through me. Uh… for some reason uh… that I’ll never know I said nothing about uh… the fact that I thought maybe this young man was Ron Tammen. I didn’t speak of it to my wife during the meal. I don’t know why I didn’t.”

H.H. Stephenson (he went by Hi, short for Hiram) knew Ron Tammen, whereas Mrs. Spivey didn’t. In 1953, Hi was the director of men’s housing and student employment. He would have interviewed Ron for his counselor’s position. He also gave Ron his permit to have a car on campus. Most of us wonder why Hi didn’t walk up to the young man when he had the chance, and he obviously would agree. But Hi told his boss, Carl Knox, the next day. Why didn’t the university follow up on that potentially big lead?

Sgt. Jack Reay, Dayton Police Department, Missing Persons [6:30]

[Describing his check on Ron’s Social Security number in 1976]

“When I checked with the state, this uh…Social Security came back negative. There was no record of it, which would indicate that, in the past few years, since we’ve had the computer, uh…and things have been entered into the computer, there’s been no activity with that Social Security number.”

The fact that Ron never used his Social Security number again is incredibly important. This means that he didn’t just run away to be with some forbidden love interest, be they female or male. If he lived—and we have evidence that he did until at least 2002—then he had to have gotten a new Social Security number, which is extremely difficult to do. There is a list of circumstances for which a person can request a new Social Security number and running away to become a new person isn’t on the list.

As I mentioned earlier, there’s a transcript of The Phantom of Oxford in Miami’s University Archives. I’m missing the first page, but I have the rest of the pages, which end at 23. The transcript appears to be written by someone in the business. It’s typewritten in two columns. On the lefthand side is a description of each video clip (photos, videotaped interviews, B-roll, and reenactments) and on the righthand side is a description of the audio (narration and interviews) that accompanies that clip. I’d always thought that the transcript was provided by someone with the TV station to the university, but now I don’t think so. I think someone affiliated with the university typed it up because they only cared about the narrative and the interviews with people tied to the university. There is one person whom they didn’t care about—Sgt. Jack Reay. Even though he wasn’t involved in the Tammen investigation, he was a great resource and had a lot to say about missing person cases. The only words typed on page 21 are “MISSING PERSON THEORY,” which covers all of Sgt. Reay’s air time. I feel that his comments are elucidating too, which is why I’ve included them here.

Sgt. Jack Reay [7:16]

[Describing how rare it is for a person to disappear completely without a trace]

“It’s very difficult for a person to just drop completely out of uh…civilization and not somebody else know who he is or where he is or something about him…or him to relate back to some of his early childhood. I’m not saying it’s impossible, I’m just saying that, percentage-wise, for someone to just completely drop out would be very small in comparison with the missings and runaways.”

Agree. I think it would have been impossible for Ron to have carried it off without A LOT of help.

Sgt. Jack Reay [8:00]

[Describing what kind of person would voluntarily leave family and friends forever]

“If somebody is really set on…getting lost, I think that they can, but they’re going to have to be a very strong individual. And as far as a 19-year-old…I don’t know. It takes an awful lot of willpower to sit back and say, there’s nothing back there that you ever want to be related to again.”

Also agree. But, as we’ve discussed numerous times, the 1950s were different. If Ron was gay, it would have been extremely difficult for him, especially if he was at risk of being outed. I honestly think that, in his 19-year-old brain, he decided that his family would be better off thinking that he was dead as opposed to being gay.

Sgt. Jack Reay [8:29]

[Describing the potential of identifying Ron’s remains decades later if he’d been a victim of foul play]

“If he was a normal individual and never really had any contacts with any type of…law enforcement or any type of identifying thing [mumbled], it would be a little bit difficult to identify that individual today. In fact it would be very difficult.”

Marcia Tammen’s DNA is on file in CODIS, the Combined DNA Index System. If there is ever a discovery of unidentifed human remains, law enforcement should be able to ascertain if it’s Ron. But, as discussed above, I also don’t think he was a victim of foul play.

Ronald Tammen, Sr. [8:42]

[Describing his thoughts with regard to ever seeing his son again]

“I…I have uh…have never lost hope that sometime, somehow something would come up so we’d have some evidence of either his death or his disappearance or the reason, reasons for it or…I’ve never given up. In fact a lot of times I’ve thought that uh…you know, he’s gonna show up. He’s gonna show up here pretty soon.”

😔

Joe Cella [9:20]

[Describing his thoughts with regard to ever finding Ronald Tammen]

“I don’t know whether I would recognize him today if…if I saw him, but uh… Richard gave me a photograph of Ron and uh…he gave it to me 23 years ago, believe it or not. I’ve been carrying it in my wallet…hoping some day in my travels around the country that, you know, who knows…it might be him coming down the street.”

I have it on excellent authority that Joe carried Ron’s photo in his wallet for the rest of his life.

**********

ADDENDUM

Carl Knox’s note in which he’s written the time of 10:30 but doesn’t mention Chuck Findlay’s name